The Rise and Defense of Optional Feature Litigation

The Rise and Defense of Optional Feature Litigation

John’s Bad Day

On a Sunday afternoon, John was driving his new 2017 base model Meerkat car when he became distracted looking for a french fry he dropped on the floor. His car crossed into the adjacent lane and, after traveling a few hundred feet, collided with a pickup truck that stopped for a woman pushing a baby carriage across the road. John is seriously injured. Once discharged from the hospital, he called an attorney to see who he can sue for the crash. The attorney discovered that a lane departure warning system and automatic emergency braking were offered as optional features on the 2017 Meerkat. John then sued the vehicle manufacturer and selling dealer for strict liability and negligence based upon claims that the car was defective and unreasonably dangerous because it was not equipped with these safety features that would have prevented his crash.

The Allure of Optional Feature Litigation for Plaintiffs

While the scenario described above is fictional, lawsuits based upon available optional features are very real. These types of claims are not new, but with the growth and rollout of new technologies, particularly in the vehicle industry, claims asserting that a product was defective and unreasonably dangerous because it was not equipped with optional features will likely increase. These types of claims are very appealing to plaintiffs’ attorneys for a number of reasons, including:

- The liability theory is pretty simple: “The option makes the product safer and would have prevented the crash and/or injuries.”

- These types of claims are prime opportunities for “reptile theory” arguments based upon couching the design hierarchy as a rule.

- The availability of the feature as optional equipment on the product provides makes it difficult, if not impossible, to argue that it is not economically and technologically feasible.

- The insurance industry and other safety advocacy groups frequently publish papers and studies on the benefits of these technologies which can be used to show “notice” of the safety benefit from the feature and the number preventable deaths/injuries/crashes which from implementation of the feature on the vehicle.

- Internal company documents may exist that tout the safety benefits and profitability of the technology in order to justify investing in research and development. These documents, in plaintiffs’ eyes, are clear evidence of the manufacturer putting profits over people.

The Design Hierarchy

The design hierarchy is the foundation upon which plaintiffs will build their case. The hierarchy is a tool engineers use for developing products, but plaintiffs attempt to transform it into a “rule” which gives rise to liability if it is not followed. Under the design hierarchy, a manufacturer should: (1) design out hazards posed by the product; (2) if the hazard cannot be designed out, it should be guarded against; and (3) if it cannot be guarded against, the manufacturer must warn of the hazard.

Plaintiffs will argue there is no need to go past the first step because the manufacturer violated the hierarchy by not making the optional feature standard equipment which would have designed out the hazard.

In John’s example above, plaintiff will argue the hazards are (a) leaving the lane due to the driver being distracted and (b) rear ending another vehicle or a striking an object in the road because the driver was distracted or did not react quickly enough. The optional lane departure warning system would have alerted John he was leaving the lane or even corrected the drift for him, and the optional automatic emergency braking would have prevented the hazard of rear ending the pickup truck. Therefore, according to John’s attorney, the manufacturer violated the hierarchy because it had the technology to design out the hazard and did not do so.

Focus on the Real Standard for Liability

In order to properly defend an optional feature claim, avoid going down plaintiffs’ path that the product is safer with the feature and, therefore, without it, the product is defective/unreasonably dangerous. Generally, a product manufacturer is not an insurer against all harm that might be caused by using the product, and the manufacturer or designer is not obligated to produce an accident-proof or injury-proof product.

Courts almost universally recognized the standard for liability is not whether a product is the safest possible product or whether it can be made safer, but whether the product, as designed or manufactured, is unreasonably dangerous.

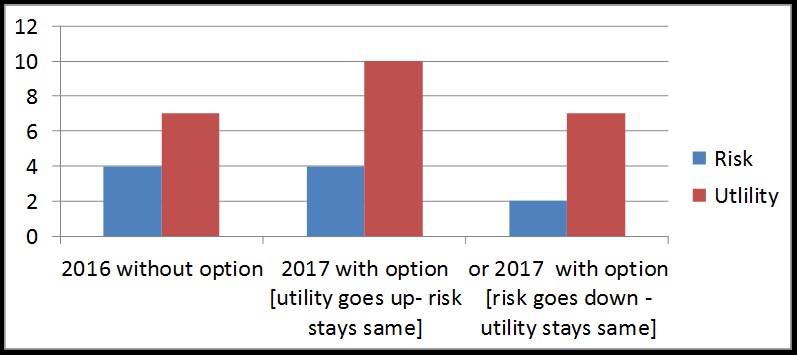

In defending the product, it is important to reinforce that the availability of a new feature does not transform a previously non-defective model into a defective one. Before the feature was introduced, users could manage the risk of using the product without the feature. The introduction of a product with the optional feature may make the utility of the product go up, or the risk go down, but the risk of using a product without the feature doesn’t change. This can be shown graphically as:

Prepare for Reptile Theory Questions

These claims are ripe for “reptile theory” questions. Examples of common “reptile” questions to expect are:

- Don’t you agree a manufacturer has a duty to make the safest possible product?

- Wouldn’t you agree a manufacturer should never needlessly endanger the public?

- Wouldn’t you want your child to have the safest [product] possible?

Be thoroughly prepared to respond to these kinds of questions. Also be prepared to address company documents which discuss the safety benefits of the option and the decision to make it optional.

Almost all engineers will admit they are familiar with the design hierarchy as it was taught in even the most basic engineering courses. However, they must be careful not to fall into the trap of elevating the hierarchy from a tool to a rule. Engineers must also be prepared to defuse plaintiffs’ description of the “hazard” and reiterate that the optional feature at issue in the litigation is merely an enhancement to an already reasonably safe product.

Highlight the Bias in Safety Advocacy/Insurance Industry Studies

Advocacy groups and insurance industry groups such as the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety and their sister entity, the Highway Loss Data Institute often publish studies advocating the benefits of safety technologies.

Plaintiffs will use these studies to support their claims. These studies, however, can have biases or be based upon inadequate data or methodologies that are skewed toward a particular outcome or finding.

The IIHS has a clear interest in reducing insurance payouts, which is evidenced by the fact that it is supported by insurers and funded by national insurance associations. See https://www.iihs.org/iihs/about-us/member-groups. The impact of these studies can be defused by highlighting the biases and flaws within them.

If Applicable, Point Out That Government Safety Standards Do Not Require the Feature

Not all products have government safety standards, but if such standards exist, the fact that they do not require the product to be equipped with the option is very persuasive evidence, and in some jurisdictions creates a presumption of non-liability. The most obvious examples are Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards and Consumer Product Safety Commission Rules. In fact, it is possible that the regulatory agency considered whether to make the feature mandatory and determined there was little to no benefit. If so, that determination will be a useful tool to rebut the advocacy studies and publications relied upon by plaintiffs.

Embrace the Consumer Expectations Test

The consumer expectation test provides that “a product is unreasonably dangerous in design…[if] it failed to perform as safely as an ordinary consumer would expect when used as intended or in a reasonably foreseeable manner. See Aubin v. Union Carbide Corp., 177 So.3d 489 (Fla. 2015) citing Restatement (Second) of Torts §402A. Under this theory, it is the expectation of the consumer and not specifically the conduct of the manufacturer that determines whether a product is defective or unreasonably dangerous.

Many times, defendants in product liability cases believe the consumer expectation test weighs in favor of the plaintiff while the risk/utility test is preferable for the defense. In optional feature claims, the consumer expectations test can be a weapon for your defense. For example, conducting a survey and review of available data to demonstrate that in 2017, 90% of similar products in use in the U.S. were not equipped with the feature is strong evidence to show that a consumer would not expect that feature to be present on a similar 2017 product.

Highlight Implementation and Efforts to Promote the Product

A feature can only provide a benefit if customers will accept it. It takes time to develop customer acceptance. “Optionality” is necessary to drive customer acceptance.

Explaining the company’s efforts to promote the feature to drive customer acceptance also presents plaintiffs with a dilemma. They want to claim that the manufacturer was greedy and made the feature optional so that it can make more money from the option, but at the same time want to claim that the manufacturer did not educate or inform the public enough to buy the option. These theories are irreconcilably inconsistent.

Make Freedom of Choice/Personal Responsibility Key Themes

Freedom of choice and personal responsibility should be central themes for the defense. Most consumers do not have infinite resources and must decide how they are going to spend their hard earned money. Considering safety options is a common component of shopping for products. Perhaps the safety option of a vehicle, affected the vehicle’s performance, the number of passengers or cargo it can carry, or significantly changed the aesthetic. Whatever the reason, consumers should be the ones that weigh the relative risk with the benefits of including the option on the product.

For example, the consumer may decide that they have been able maintain their lane of travel without assistance for years and, instead of spending money on a lane departure warning system, may choose to spend money on a better child safety seat, a backup camera or a home security system. People are entitled to make their own decisions on how to spend their “safety” dollars and to make choices about their risk tolerances.

Tell the Story Regarding the Real Increased Cost of the Optional Features

A plaintiffs’ attorney will claim that the cost of the optional feature is simply the sum of the component parts. This overly simplified position does not take into account the research and development that goes into designing and testing the parts.

Additionally, point out the other costs to consumers of the optional features. On October 25, 2018, the American Automobile Association released findings that vehicles equipped with advanced driver assistance systems, such as automatic emergency braking and lane departure warnings, can significantly increase the cost of repair, even for minor vehicle collisions.

“For the vehicles in AAA’s study, the repair bill for a minor front or rear collision on a car with [advanced driver assistance systems] can run as high as $5,300, almost two and half times the repair cost for a vehicle without these systems.” According to AAA, “[w]ith one-in-three Americans unable to afford an unexpected repair bill of just $500, AAA strongly urges consumers to perform an insurance policy review and consider the potential repair costs of these advanced systems.” When used in conjunction with freedom of choice, the added cost to repair can be a compelling justification in support of optionality.

Case Precedent for Optional Feature Claims

Courts in many jurisdictions have recognized that a manufacturer should not be liable for a consumer’s choice not to purchase an available optional feature, even where the optional feature would make the product safer. For example:

- “A manufacturer is not obligated to market only one version of a product, that being the very safest design possible. If that were so, automobile manufacturers could not offer consumers sports cars, jeeps, or compact cars…Personal safety devices, in particular, require personal choices, and it is beyond the province of courts and juries to act as legislators and preordain those choices.”— Linegar v. Armour of America, Inc., 909 F.2d 1150, 1154 (8th Cir. 1990) (applying Missouri law).

- “Put simply, if the [plaintiffs] wanted a car with an air bag, they should have purchased a car with an air bag. If you want it, then pay for it.”— Cooper v. Gen. Motors Corp., 702 So.2d 428, 443-44 (Miss. 1998).

- “[W]hen a customer exercises an option to purchase a product without a safety feature, it is axiomatic that the manufacturer should not be held liable for damages which that safety feature may have prevented.”— Austin v. Clark Equip. Co., 48 F.3d 833, 837 (4th Cir. 1995) quoting Butler v. Navistar Int’l Transp. Corp., 809 F. Supp. 1202, 1209 (W.D. Va. 1991).

Key Takeaways

With the proliferation of advanced technologies in motor vehicles, manufacturers can expect an increase in litigation by consumers who purchased products where these features were not available or were optional, and who claim they were injured because of the absence of the feature. These cases are attacks on the corporate decision-making strategy and can create significant exposure to manufacturers if not properly defended.