Celebrating Black History Month: Court Cases that Made History

Celebrating Black History Month: Court Cases that Made History

As a trial firm, we have an appreciation for court cases and have chosen a few cases that impacted not only the respective local communities, but also inspired change and moved the needle toward civil rights for African Americans. Each week during Black History Month, we will feature another case from one of our local communities.

Wimbish v. Pinellas County, Florida, 342 F.2d 804 (5th Cir. 1965)

This case to integrate county-owned golf courses was argued by St. Petersburg and Pinellas County’s first Black lawyer, Fred G. Minnis, Sr., who also represented students arrested for participating in sit-ins at the Webb’s City lunch counter.

Background:

Defendant Pinellas County, Florida, leased certain of its undeveloped lands, which were adjacent to the County airport but not used for any part of the airport or for any other County purpose, to defendant Airco Golf, Inc., a Florida corporation. Defendant Airco Golf, Inc., as lessee, was obligated to use the premises only for a golf course, and it agreed to develop the property for that purpose and to construct, maintain and operate a regulation golf course thereon. The district court found that the plaintiffs were denied the right to play golf on the said golf course by the management solely because the plaintiffs were African Americans, while at the same time white persons have been permitted to play golf on the course. The primary question on appeal was whether the action of defendant Airco Golf, Inc., in denying the plaintiffs the use of the golf course, because of their race, is “state action” and thus prohibited by the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution. The district court held that the operation of the golf course was not “state action” and dismissed the plaintiff’s complaint, which requested an injunction enjoining the defendants from denying the plaintiffs and others similarly situated the right to use the golf course, solely on account of their race.

Holding:

The Court held, that “when there is no purpose of discrimination, no joinder in the enterprise, or reservation of control by the county, it may lease for private purposes property not used nor needed for county purposes, and the lessee’s conduct in operating the leasehold would be merely that of a private person.” Derrington v. Plummer, 5 Cir. 1956, 240 F.2d 922, 925. Pinellas County executed the lease on July 18, 1961. The initial term was for twenty-five years with the right of renewal for an additional fifteen years. The lease provided that the “demised premises shall be used only for the construction and operation of a golf course and related facilities and the Lessee agrees to place improvements on said premises for said purposes.” The plans and specifications for all improvements constructed on the premises must be submitted to and approved by Pinellas County and title to all improvements made on the property vests in the County. The prices charged for golf fees “shall not be reasonably less than or reasonably greater than prices which are customary and reasonable in the trade for comparable merchandise, service and facilities.” The prices are subject to the approval of Pinellas County and are subject to review at any time by the County. Airco Golf, Inc., is required to establish daily memberships or green fees so that the use of the facilities will not be confined to persons holding memberships for a longer term. By these provisions the Court felt the County had joined in the golf-course’s enterprise to such an extent that the Equal Protection Clause must be applied to Airco Golf, Inc.’s conduct in operating the leasehold. The judgment of the district court was reversed and remanded.

Shepherd v. Florida 341 U.S. 50 (1951) aka The Groveland Four Case

Background: In 1949 four young black males were wrongly accused of raping a 17-year old white woman. On September 2, 1949 the trial of State of Florida versus Shepherd, Irvin, Greenlee, and Thomas was set to commence in Lake County circuit court. The three surviving men faced an all-white, all-male Lake County jury who heard just two days of testimony (Thomas was killed prior to trial by a Madison County law enforcement posse, there were four different types of ammunition identified in his body). Fearing a Black attorney may be seriously injured or killed if he rose to cross examine a white woman in front of a white jury, the NAACP’s Franklin Williams and later Thurgood Marshall were sidelined in favor of their white co-counsel who was unable to overcome the overwhelming biased court and jury panel. From the outset, the defense team was disadvantaged by the fact that southern courtroom essentially required them to limit their defense to that of mistaken identity (they were also forced to concede a rape occurred when evidence to the contrary existed). Greenlee was sentenced to life due to his age (16) at the time of the alleged crime; Shepherd and Irving were sentenced to death. Due to the obvious lack of evidence and undue influence of the Lake County court, media, and police the United States Supreme Court eventually took on the issue.

Holding: On April 9, 1951, the United States Supreme Court reversed the convictions in the case of Shepherd v. Florida. The opinion overturned the convictions unanimously on the basis of improper grand jury selection procedures, Justice Robert H. Jackson argued that improper pretrial publicity in the local press could have also constituted a basis for reversal. The case was remanded back to Lake County. Sadly, the continued media forces and dominant policing force of Lake County remained ever present in the local re-trial. Prior to the re-trial in Lake County the Lake County Sheriff shot and killed Samuel Shepherd during what would have been a routine armed transport back to Lake County Jail for trial; Walter Irvin somehow survived the transportation incident and relayed his account of the shooting to representatives of the NAACP from his hospital bed in Eustis. Even with the representation of Thurgood Marshall, Irvin was again convicted by another all-white jury and sentenced to death (eventually gaining parole in 1968).

In 1955, Irvin’s death sentence was reduced to life in prison. He was paroled in 1968, but died the next year in Lake County. Greenlee was paroled in 1962 and lived with his family until he died in 2012. In 2016, the City of Groveland and Lake County formally apologized to survivors these men’s families. On April 18, 2017, the Florida House of Representatives requested that all four men be exonerated; The Florida Senate passed a similar resolution. On January 11, 2019, the Florida Board of Executive Clemency voted to pardon the Groveland Four. In 2021, after years of public outcry, Lake County State Attorney Bill Gladson filed a motion asking a judge to dismiss the original indictments against Thomas and Shepherd and set aside the judgements and sentences handed out to Greenlee and Irvin.

Shuttlesworth v. City of Birmingham, 394 U.S. 147 (1969)

Background:

In Shuttlesworth v. City of Birmingham, 394 U.S. 147 (1969), the United States Supreme Court overturned the conviction of civil rights leader, Fred Shuttlesworth for violating the City of Birmingham’s ordinance making it an offense to participate in a public demonstration, parade or procession without first obtaining a permit from the city commission. On Good Friday in 1963, Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth, along with two other Black pastors, led 52 Black marchers out of a Birmingham church in an orderly civil rights march, which did not obstruct or impede traffic, to protest the denial of civil rights to Black people in the City of Birmingham.

At the end of the march, the marchers were arrested by Birmingham police for violating the ordinance. At the time, the ordinance gave the city commission unfettered and absolute discretion to deny permits if “in its judgment the public welfare, peace, safety, health decency, good order, morals, or convenience require that it be refused.” Id. at 149 (quoting ordinance). Reverend Shuttlesworth was sentenced to “90 days’ imprisonment at hard labor and an additional 48 days at hard labor in default of payments of a $75 fine and $24 costs.” Id. at 150.

Holding:

The Alabama Court of Appeals reversed the conviction finding among other things that the ordinance “had been applied in a discriminatory fashion and that it imposed an unconstitutional ‘invidious prior restraint’ without ascertainable standards for the granting of permits.” Id. In 1967, four years after the conviction, the Alabama Supreme Court, gave the ordinance a very narrow construction, reversed the Alabama Court of Appeals, and reinstated Reverend Shuttlesworth’s conviction. Id.

While the United States Supreme Court found that the Alabama Supreme Court had “performed a remarkable job of plastic surgery upon the face of the ordinance” and that its new narrow interpretation transformed the ordinance into an “objective and even-handed regulation of traffic on Birmingham’s streets”, it held that the Alabama Supreme Court’s narrow interpretation of the ordinance in 1967 did not give constitutional validity to a conviction that occurred four years earlier, in 1963, under the ordinance as it was written. See id. at 154-55. Noting that Reverend Shuttlesworth was clearly given to understand in 1963 “that under no circumstances would he and his group be permitted to demonstrate in Birmingham,” the Supreme Court found that the ordinance was administered “to deny or unwarrantedly abridge the right of assembly and the opportunities for the communication of thought . . . immemorially associated with resort to public places” and reversed the conviction. Id. at 158-59.

Read the opinion.

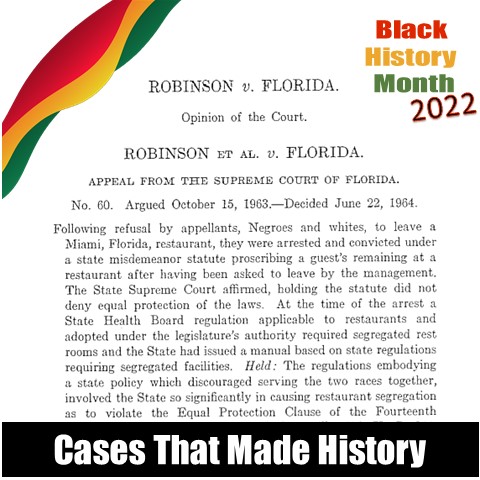

Robinson v. Florida, 378 U.S. 153 (1964)

Background: Eighteen white and African American persons went to a restaurant in Shell’s Department Store in Miami, Florida. Consistent with the restaurant’s policy of refusing service to African Americans, the restaurant manager requested the persons to leave. When they refused, they were arrested for violation of a statute allowing a restaurant to have a right to remove any person that it considered detrimental to serve. At trial the defendants argued their arrest, prosecution, and conviction by the state for requesting service at a restaurant that refused service to African Americans would violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The trial court stayed the adjudication of guilt and, consistent with state law, placed them on probation. On appeal, the Supreme Court of Florida affirmed, holding that the statute under which the convictions were made was nondiscriminatory and thus did not violate equal protection.

Holding: The case was brought before the Supreme Court of the United States which reversed the convictions of the individuals. The Supreme Court considered its prior ruling in Peterson v. Greenville, 373 U.S. 244 (1963), which ruled that a state law making it unlawful for restaurants to serve black and white persons in the same room or at the same table or counter constituted state action in violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Florida had a regulation requiring any restaurant to have separate toilet and lavatory rooms for each race or sex served or employed. While this regulation did not directly and expressly forbid restaurants from serving both white and Black people together, it burdened any restaurant serving both races, a state action in violation of the Equal Protection Clause as stated in Peterson.