Defense Strategies When Confronting the Perils of an Inconsistent Verdict

Defense Strategies When Confronting the Perils of an Inconsistent Verdict

New decision by the Florida Supreme Court Eliminates Important Defense Protection in Cases Involving Inconsistent Verdicts

On May 14, 2015 the Florida Supreme Court eliminated an important protection for product liability defendants in design defect cases that produce inconsistent jury verdicts. The court’s decision in Coba v. Tricam Industries, Inc., jettisoned Florida’s unique, “fundamental nature” exception to the requirement that counsel must object to an inconsistent verdict before the jury is discharged. This article discusses the risks of inconsistent verdicts in product liability design defect cases and the strategies that defense counsel of any jurisdiction can employ when confronting the perils of an inconsistent verdict.

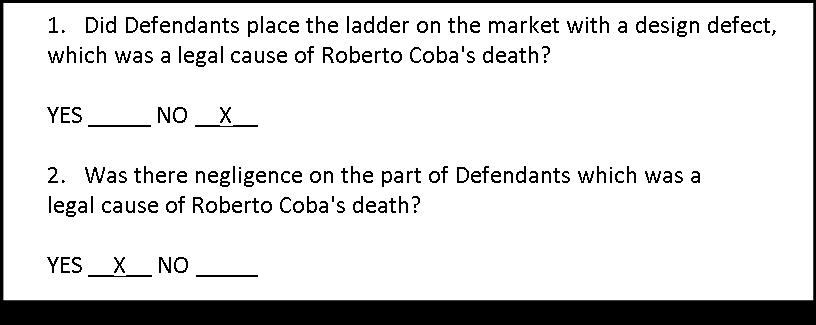

In Coba, plaintiff brought a wrongful death products liability action against the manufacturer of an aluminum ladder. The case went to the jury on two theories: strict liability for a design defect and negligence for the failure to design the ladder in a reasonably safe condition. At the conclusion of the evidence, the trial court authored a verdict form for the jury to use in deliberations. The following reflects the jury’s key entries on the verdict form in Coba:

After entering their conclusions on the verdict form, the Coba jury returned a seven-figure award and they were discharged by the trial court without objection from defense counsel.[1] The manufacturer-defendant subsequently filed a motion to set aside the verdict as inconsistent.[2] Because plaintiff’s liability theory was based exclusively on a design defect, the manufacturer argued that the jury’s finding of negligence was fundamentally inconsistent with its conclusion that there was no design defect.[3]

The appellate court agreed and granted the manufacturer’s motion. The appellate court acknowledged the general rule that a party waives an objection to an inconsistent verdict if it fails to raise the issue before the jury is released.[4] However, the court applied a common law exception adopted by other Florida appellate districts in cases where the verdict inconsistency was “of a fundamental nature.”[5] The appellate court determined this exception was present in Coba because plaintiff had limited its presentation of trial evidence solely to a purported design defect.[6] Thus, when the jury found no evidence of an actionable design defect, the inconsistent finding of negligence was fundamentally unsupportable. The appellate court concluded that the failure to contemporaneously object did not waive the right to challenge a verdict inconsistency of such a fundamental nature.[7] The court then resolved the inconsistency in favor of the defense rather than remanding the case for a new trial. The appellate court reasoned that because plaintiff only put on evidence of a design defect as the basis for the products liability claim, the jury’s failure to find a defect meant “there was no evidence to support any other cause of action [and] no issue to be resolved on remand.”[8]

The Florida Supreme Court overturned the appellate court and held that there is no “fundamental nature” exception to the waiver that occurs when the defendant fails to object to an to an inconsistent verdict before the jury is discharged.[9] The Supreme Court determined that a “fundamental nature” exception in products liability cases is “at odds with the [….] policy reasons undergirding the requirement of timely objection, including upholding the sanctity of the jury’s role in trial, preventing strategic gamesmanship, and increasing judicial efficiency.”[10]

In part, the Supreme Court based its ruling on a desire to prevent defense counsel from “strategically sitting on the objection until after the jury is no longer available to correct its decision.”[11] The court ignored however, the strategic practice by which plaintiffs’ counsel present superfluous liability theories in design defect cases to emphasize multiple grounds for recovery on the verdict form despite the risk of inconsistent verdicts.[12] Such tactic may involve a wager that the defense will not recognize the problem in the frenetic moments between verdict announcement and jury discharge in order to timely object.[13]

Moreover, trial is a considerable interruption to the personal lives of the jurors and when verdict is announced, a powerful momentum arises to terminate their service and swiftly return them to their real lives. In this atmosphere, there is a clear disincentive for defense counsel to demand the jury return to deliberations to reconsider a verdict in which they have already signaled at least partial favor for plaintiff’s case. When a judge requires a jury to reconsider their verdict, they are not bound by former conclusions on the verdict form and they are free to comprehensively review the case and bring an entirely new verdict.[14] In such a situation, defense counsel certainly risks jury reprisal by impeding the conclusion of their service by obligating them to reconsider a verdict inconsistency.[15]

With these considerations in mind, the following strategies should be employed by defense counsel of any jurisdiction when confronting the perils of an inconsistent verdict (regardless of the cause of action):

- First, defense counsel must be cautious about special verdict forms especially where authored by opposing counsel or the judge. The popularity of special verdict forms with multiple interrogatories continues to grow in modern litigation.[16] However, the increased use of such verdict forms comes with an attendant rise in the risk of the jury issuing inconsistent answers to the verdict interrogatories.[17] For example, on the Coba verdict form, the first interrogatory unwisely asked the strict liability question without reference to the “unreasonably dangerous” terminology which defines product defectiveness in Florida.[18] Had such terminology been included in the first interrogatory question, the Coba verdict form might have emphasized the need for the negligence interrogatory to be answered consistently. Additionally, the form needlessly prompted the jury to proceed to the second interrogatory about negligence even if they did not find an actionable design defect in the first. Considering the case presented at trial, the Coba verdict form should have directed the jury to proceed no further if they gave a negative response to the first interrogatory.[19] The bottom line is that defense counsel must closely examine draft verdict forms for the potential of inconsistent jury conclusions considering the associated jury instructions and the evidence proffered by plaintiff during trial.

- In light of the frenzied atmosphere that typically unfolds at the announcement of the verdict, defense counsel must take advantage of the opportunity to be more deliberative in evaluating the draft verdict form when litigated in relative repose earlier in the trial. At that time, defense counsel should also be unsparing in raising appropriate objections to the substance of verdict form entries drafted by the court or opposing counsel. Pertinent objections to the verdict form have the capacity to also preserve an appellate challenge to a subsequent inconsistent verdict by the jury.[20]

- When there is a prospect of an inconsistent verdict, advance efforts must be made with the judge to:

o avoid a post-verdict environment in which defense counsel must precipitately evaluate the presence of a verdict inconsistency; and,

o mitigate jury aggravation should they be required to return to deliberations to resolve an inconsistency.

- Examples of such advance efforts include: (a) avoiding scenarios whereby the jury enters deliberations likely to culminate at the close of business or the end of the work week, (b) asking the judge to affirmatively warn jurors in the instructions that they may have additional post-verdict responsibilities (or at a minimum, asking the judge and opposing counsel to refrain from comments to the jury which create an expectation that their work is concluded the moment they announce a verdict), (c) a preemptive request to the judge – before jury deliberations – that counsel receive a sufficient moment, outside the presence of the jury, to consider any verdict inconsistency before jury discharge.

- Once the verdict form is provided to the jury, defense counsel must anticipate the scenarios that could result in an inconsistent verdict no matter how theoretical. Questions raised by the jury about the form during deliberations must be scrutinized for signs of a looming inconsistent decision. Defense counsel should use the time during jury deliberations to research the standard applicable to the possible verdict inconsistencies and to formulate the objections and arguments to be made before jurors are discharged.

- If the jury is discharged without defense objection, there is still the possibility of a motion for judgment in favor of the defense notwithstanding the verdict (“motion for JNOV”).[21]

o For example, before the jury ever receives the case, it is now a standard practice for defense counsel to move for directed verdict arguing that plaintiff’s evidence was insufficient to give the case to the jury.[22]–[23]

o When a verdict inconsistency is then recognized only after the jury is discharged, defense counsel should consider whether such inconsistency illustrates, in and of itself, the absence of sufficient evidence to support that portion of the verdict which favored plaintiff. A motion for JNOV is appropriate in cases where the reasonable jury could not render a plaintiff’s verdict based on the evidence introduced at trial.[24] Therefore, provided the defense made the standard motion for directed verdict at the close of plaintiff’s case, there remains a post-trial JNOV attack[25] on an inconsistent verdict on grounds that the contradiction manifests a lack of evidence to legally support that portion of the verdict for plaintiff.[26] Such grounds are preserved even where defendant waived the inconsistent verdict objection.[27]

A difficult predicament arises for defense counsel when the perils of an inconsistent verdict arise at trial. For the products liability defense attorney, this is most likely to occur in the design defect case where plaintiff needlessly presents both strict liability and negligence claims as to the same defect theory. As a result of the Coba decision, Florida now joins other jurisdictions which require the defense to object before jury discharge in order to make an appellate challenge to an inconsistent verdict. However, by employing the strategies discussed above, defense counsel can minimize the dilemmas resulting from this requirement and perhaps transfer back to plaintiff, the risk of post-trial consequences of the inconsistent verdict.

[1] Id.

[2] In Florida, an inconsistent verdict occurs “Where the findings of a jury’s verdict in two or more respects are [….] such that both cannot be true and therefore stand at the same time….” See id. at * 6 quoting Crawford v. DiMicco, 216 So. 2d 769, 771 (Fla. 4th DCA 1968).

[3] Tricam Industries, Inc. v. Coba, 100 So. 3d at 108.

[4] Id. at 108-09.

[5] Id.

[6] Id. at 110-11.

[7] Id.

[8] Id. at 108-09.

[9] Coba, 40 Fla. L. Weekly S257a. at *1

[10] Id. at *8.